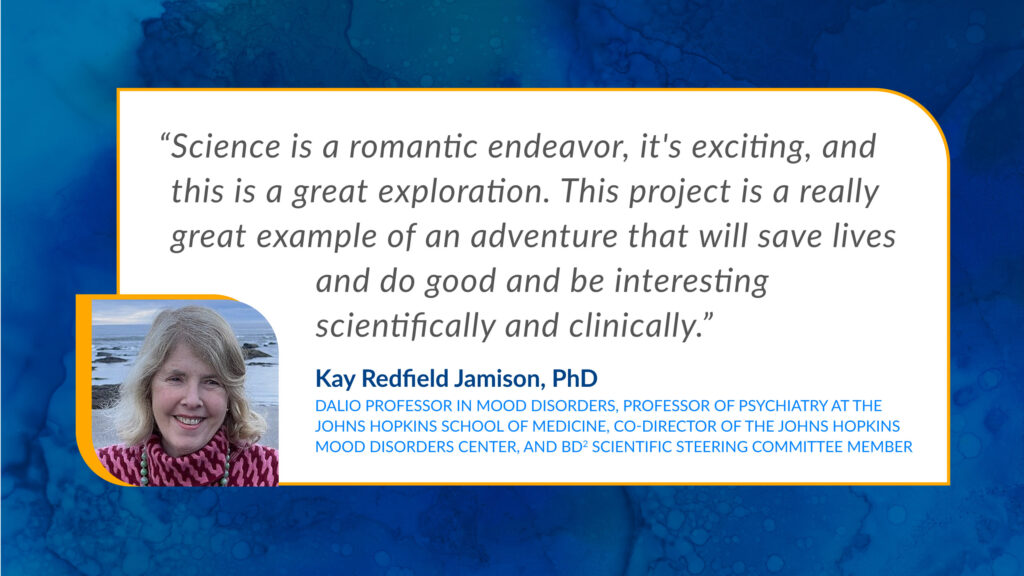

An Interview with Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, for World Bipolar Day

World Bipolar Day was declared on March 30, 2014, as a day to bring awareness to bipolar disorder and to eliminate social stigma and discrimination.

BD² recognizes World Bipolar Day as a reminder of our shared vision: that all people with bipolar disorder thrive. In honor of World Bipolar Day and the first participants joining BD²’s Integrated Network longitudinal study this month, we spoke with Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, a BD² scientific steering committee member who has written eloquently and movingly about her own experiences with bipolar disorder, helping bring greater awareness to it and other mood disorders.

Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, is an author, the Dalio Professor in Mood Disorders and Professor of Psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Mood Disorders Center, which is part of the longitudinal study.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you hope people know or understand about bipolar disorder?

It’s important to know that [bipolar disorder] was described thousands of years ago. It’s been around as long as people have observed behavior. I am often struck by the fact that people have no idea how much good science backs up what we know about bipolar illness. People have been studying [bipolar disorder] for a long time. There were 60 doctoral dissertations written before 1700 or 1750 on mania. We tend to think of it as a modern disease, and I think that leads to a lot of difficulties and a peculiar kind of stigma of not appreciating how much it is part of human history.

It’s important to realize it’s common. There’s this notion that mania and depression are uncommon or certainly that mania is uncommon, and that is not true. The bipolar illness spectrum is associated with a lot of very damaging things, most importantly suicide, but also alcohol and drug use and violence. It’s a very early onset illness, so unlike dementia or heart disease, which hit people much later in life, these hit people when they’re young. They have to cope with [bipolar disorder] when they’re young, and they don’t have the experience of life to help them out. That tends to be overlooked, what it does to people and their families, and how devastating it is. First and foremost, I would want people to know that it’s treatable, imperfectly treatable, but treatable, and it’s important to get it treated.

What’s the impact of the BD² Integrated Network longitudinal study recruiting its first participants? How do you think BD² will make a difference in the lives of people with bipolar disorder?

The very fact that it’s being done means that a very serious illness is being taken very seriously. So if you’re a patient, and I count myself in that category, the fact that people are investing time, effort, imagination, and money into studying an illness over many years is deeply wonderful. That’s just something in terms of the morale of patients, to know that this is going on. There aren’t any guarantees. It’s the nature of science. But in an ideal world, people will learn more specifically how to make very precise diagnoses that can result in much more precise treatments.

[Scientists and clinicians] want to be able to do what we know now with much more precision, and then you want to be able to characterize the illness much more carefully.

How does BD² build upon our current understanding of bipolar disorder?

It organizes the effort. I think we’re at a point where it makes sense to combine a very large number of patients. The scientists who are involved in this effort are flexible, and they understand the clinical aspects of the illness, which is very important not just for treating patients but also for research, that you understand what the manifestations are, the varieties, and so forth. It’s an exciting adventure and an effort that involves a lot of people, a lot of time, a lot of money, and it’s very exciting.

How does connecting the experiences of people with bipolar disorder to clinical work move the research forward?

I think a lot of good research is based on observation, and observation comes from doctors observing patients, but it also comes from patients observing themselves and putting it into words. I’ve used the writing of writers to describe mania to people for years, ever since I started teaching practically because if you ask a clinician what mania is, it’s going to be a long distance from what a patient will describe it as.

It is just a different kind of experience. The differences between bipolar I, bipolar II, and different kinds of sleep disorders, are described brilliantly by many writers in a way in which you just don’t see in the clinical literature. Reading the DSM-V description of mania, it’s not interesting. It’s boring. It’s important. It’s necessary. You need it for research. You need it for clinical practice. But it’s only one small part of describing the syndrome.

If someone is recently diagnosed with bipolar disorder, what are some thoughts or pieces of wisdom you would share?

It’s completely reasonable to extend hope to somebody who has bipolar illness but to also make it very clear that it’s hard. But draw upon what you know. Read, read, read. Learn about it. Badger your doctors. Why are they doing this? What’s the point of this drug rather than that drug? Always question what’s happening to you. But, again, this is an illness that has an incredible amount of not just scientific work but written discussion. I think one of the many awful things about having a mental illness is that you feel very alone with it, and one of the things that literature always has done is to make people feel less alone with whatever it is that they are going through.